Such a perfect autumn day was hard to believe after all the bad weather over preceding days. I had prepared myself for the disappointment of another cancellation but no, on this mild, calm October evening, the ‘Wild About Loddiswell’ canoe trip was going to happen.

Gathering on Newbridge Quay at Bowcombe in Kingsbridge, I received an enthusiastic welcome from Dave Halsall; host of our trip, excellent naturalist and owner of Singing Paddles. Dave and I have known each other for many years through our involvement on the Salcombe - Kingsbridge Estuary Forum, where he has been a regular contributor, reporting both wildlife highlights and environmental concerns observed through his regular presence on the water, helping to inform both management and protection of our beautiful landscape.

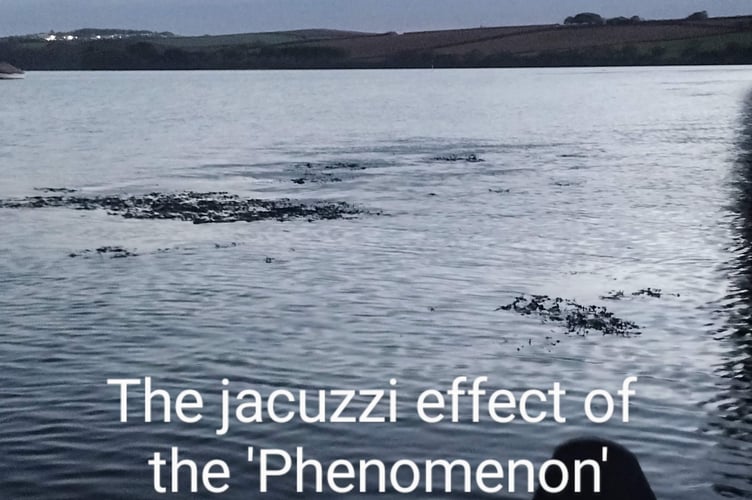

Canoes launched, lifejackets donned and paddles selected, we boarded and set off through the fading daylight. Dave demonstrated the key paddle strokes for the benefit of novices and then, after a bit of practice, we headed out towards High House Point where the town cemetery comes down to the water. As we approached the promontory, dark patches of disturbance could be seen on the water’s surface. Moving closer, a strange bubbling sound could be filtered out from the rustling of leaves above. What could it be? A strange gaseous emanation from the adjacent burial ground, perhaps?

Clustered above the outpourings of bubbles, as if in a natural (but rather chilly) jacuzzi, Dave explained that below, there was an area of porous rock. During high tides, water displaces the air trapped inside, creating the spa effect. On this occasion it was a fairly gentle experience but on other trips, the force of bubbles flooding out has made the whole canoe vibrate, creating a resonant thrum throughout its hull.

Returning to the quay for refreshments before heading under the bridge for the second part of the evening, I spotted a large flying bat silhouetted against the sky. It was too big for a Pipistrelle; a Noctule maybe? Whatever it was, it boded well for getting out the bat detectors further up the creek.

Dave lit the Kelly Kettle, laid out cakes and cookies, and took orders for hot drinks. The light was nearly gone but looking upstream, the darkest areas of shadow suggested that the tide was now very high and it would be a squeeze to get under the barnacle-encrusted arches of the road bridge.

Refuelled with hot chocolate and cake, we paddled upstream, lying back in our canoes to pass beneath the arches, happily with no crustacean-related incidents. Lighting from the waterside houses made it hard to establish good night vision and it was a relief to make it up to Bowcombe Bridge and the top of the navigable water where bank vegetation shielded us from their distracting effects. With bat detectors switched on, we listened to the white noise expectantly. Despite the mild temperature and stillness of the night, there was very little bat activity. A few flurries of progressively rapid clicks from the direction of the treeline indicated that some Pipistrelles were out moth-hunting, shouting into the darkness and echo-locating their prey from the bounce-back of sound received by their super-sensitive ears.

Turning off the electronic crackle, we lay back in our canoes to gaze silently at the night sky. Slate clouds drifted and parted, revealing the jet black firmament beyond. Constellations emerged and vanished and the Milky Way’s faint path could be made out, not by looking at it directly but slightly obliquely, using the light sensors in the periphery of our eyes which are more sensitive in low light conditions. Satellites tracked systematically across the sky and a shooting star or two made a fleeting appearance.

Paddling back downstream, we started to look for bioluminescence twinkling in the water as we swished our paddles gently. Autumn is a good time to see it as it is when the sea is at its warmest. Searching out the darkest areas, under trees, back under the bridge and finally, close to the gabion wall opposite the quay, we were rewarded with ephemeral green sparkles winking on and off as the water was disturbed. Dave explained that this was produced by dinoflagellates, a type of bioluminescent algae which produce a chemical reaction, generating light in response to disturbance. The theory is that the light may scare or confound predators so they move away, or it may illuminate them so they become prey for another predator - clever stuff. I was struck by the electric green hue, identical to that of glow-worms, and Dave went on to add that in other places, electric blue is the predominant colour. I have seen it on rare occasions, as waves break onto a beach after sunset: a magical experience akin to the auroras.

It was a truly special evening.